Spoofing, Spying, and Encryption In Government Devices

What Are You Really Protected From?

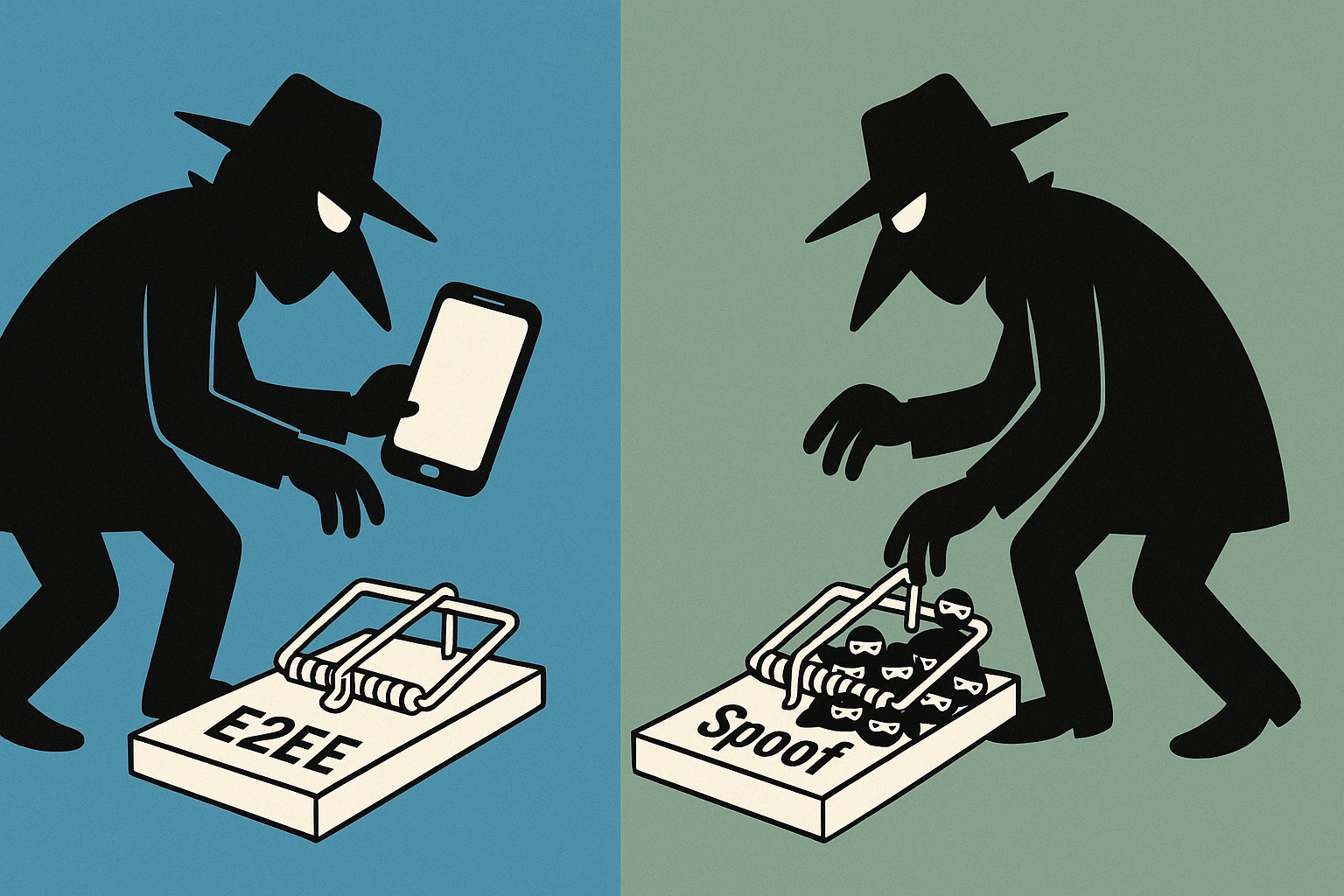

Recent headlines have reignited debate about the security of encrypted messaging apps like Signal, particularly following reports that Secretary of State Marco Rubio was impersonated via a voice AI app to manipulate high-profile officials. While the details of this story remain murky, it provides a useful lens to examine the distinction between spoofing and end-to-end encryption (E2EE) – and what each actually protects against.

What Is End-to-End Encryption?

End-to-end encryption is a security protocol that ensures only the communicating users can read the messages sent between them. No third party – including the app provider, hackers, or government agencies – can decrypt the content while it’s in transit.

Protects against: Interception of messages by outsiders, mass surveillance, and unauthorized access by service providers.

Does NOT protect against: Someone pretending to be someone else (spoofing), or a compromised device at either end.

What Is Spoofing?

Spoofing is the act of impersonating another person or entity in digital communications. This can happen in various ways:

Username or account spoofing: Creating an account that appears to belong to someone else.

Caller ID or phone number spoofing: Making messages or calls appear to come from a trusted number.

Voice spoofing: Using AI-generated voices to mimic someone in calls or voice notes.

Protects against: There is no direct “protection” from spoofing via E2EE; rather, authentication and verification mechanisms are needed.

Why End-to-End Encryption Can’t Stop Spoofing

E2EE ensures the message content is private, but it does not verify the identity of the sender beyond what the app presents. If an attacker gains access to a trusted account (through social engineering, SIM swapping, or by registering a new account with a similar name or number), their messages are encrypted and delivered just like any legitimate message.

Example scenario:

If someone registers Signal with a throwaway phone number they control, but names it “Marco.Rubio@state.gov,” it could theoretically trick an unsophisticated aid or elected official. The app cannot distinguish between the real Rubio and the impersonator.

The Role of Authentication

It is incumbent on all people, especially those in sensitive positions like governors, Congress members, and foreign ministers, to be aware of spoofing dangers. Recognizing the difference between a username, alias, and verifiable contact information is hard for many people these days.

To mitigate spoofing, very secure messaging apps often offer additional authentication features:

Safety numbers / security codes: Users can verify each other’s identity by sharing codes.

QR code scanning: In-person verification to ensure contacts are genuine.

Profile verification: Some platforms allow for verified profiles, Signal does not, despite being used as a government product.

Was This A Scammer Or Rubio In Disguise, As Himself?

A key question in the recent story is how the alleged impersonator obtained the Signal contacts or phone numbers of so many officials. Spoofing an identity on Signal is easy. Acquiring the contact information of an elected official on Signal, is not. Signal accounts are tied to phone numbers, and adding someone as a contact typically requires knowing their number. They do not get “sucked in,” as former National Security Advisor Mike Waltz claimed during the first Signalgate scandal.

Gaining access to a network of high-level officials’ numbers is non-trivial and would likely require:

- Insider Access

- Leaks

Compromised Devices - Social Engineering

This difficulty raises skepticism about the narrative that a random scammer could have pulled off such a widespread operation.

The more likely scenario is that Marco Rubio himself was using the app to contact these government officials. Why this story is being presented, would be intent (on Rubio’s part) on seeding disinformation so that Trump or others would disbelieve he really said this thing or that.

The fact that the story broke from a cable The Washington Post received (no explanation about how/where/why or what a “cable” really means today) and contained no real context, is suspicious.

If there is really a person out there using encrypted communications apps to communicate with foreign leaders in such a way that the State Department cannot contain or control, that would be an incredible story. However, in lieu of that, I think it is still important for the public to understand the differences between these attack styles, and why Signal continues to be a decent product with a bad reputation.

Public Perception: Is Signal Insecure?

When stories like this break, the public often conflates the app’s security with the actions of users or attackers exploiting social engineering.

In reality, Signal’s encryption remains robust against interception. Spoofing is a separate threat vector that targets human trust, not cryptographic weakness.

Key Takeaways

End-to-end encryption protects message content, not sender identity.

Spoofing exploits trust and identity verification gaps, not encryption flaws.

Effective security requires both strong encryption and diligent user authentication.

High-profile cases of impersonation often involve social engineering, not technical compromise of the app. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for accurately assessing both the strengths and limitations of secure messaging platforms in today’s threat landscape.